By John Bozzella

Pity the policymaker responsible for regulating U.S. vehicle tailpipes at the dawn of the electric age.

It’s a tall order.

Balancing climate. With global competitiveness. And the specter of China. While preserving a consumer’s ability to choose a vehicle that works for them. All complex considerations.

It’s tougher still when you layer in a choppy U.S. electric vehicle market (not surprising as we move beyond early adopters)...

And the politicization of EVs in an election year (an unfortunate reality)…

And oil interests committed to the status quo (predictable).

So, I’m not going to bash EPA’s final greenhouse gas emissions and criteria pollutant rules for light-duty vehicles covering model years 2027 through 2032.

Three observations about the just announced six-year standards:

- It’s the most consequential carbon reducing policy for vehicles… ever.

- It’s significantly different from the unworkable plan the Biden administration originally announced about a year ago.

- It’s still going to be very challenging to achieve given the scale of the industrial base transformation and massive amounts of capital required, the public charging and supply chains still getting ironed out, and the change in consumer behavior ultimately needed to succeed.

Where did it end up?

I’d call it: the ragged edge of achievable – but only if everything I cited above goes just right.

Let’s get into it:

Returns EV targets to Biden’s 2021 Executive Order…

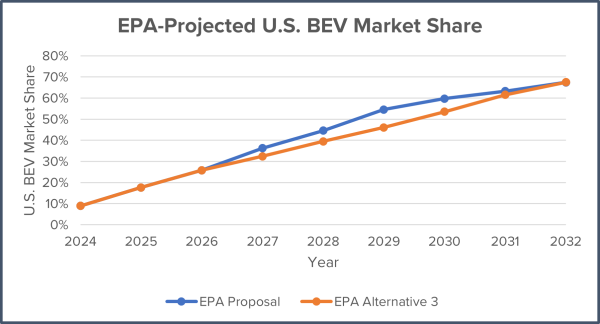

EPA’s original proposal estimated about 37 percent battery EV sales by 2027, 60 percent by 2030 and 67 percent by 2032.

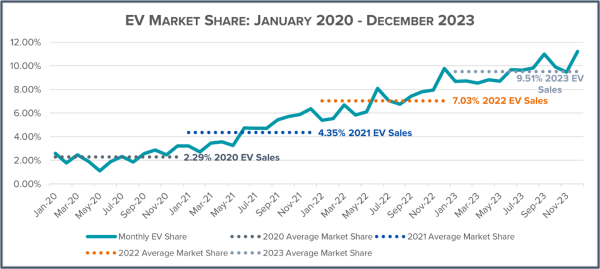

Remember: EVs are about 10 percent of the U.S. market today.

Source: Get Connected Electric Vehicle Report Q4 2023 (coming soon)

In 2023, EPA outlined four alternatives for the new emissions rules.

It looks like they landed on ‘Alternative 3’ from the proposal, the most linear of the EV adoption scenarios through 2032 (and what we thought made the most sense).

That brings EPA’s final rule closer to a 50 percent EV sales target by 2030 (down about 10 points from the proposal).

That’s a revision more in line with President Biden’s 2021 executive order and the administration’s 2023 National Blueprint for Transportation Decarbonization.

Pace matters…

Where we are (or aren’t) in 2032 is unclear at this point.

I know this: the targets are extraordinarily ambitious. But what’s more pressing is for the country to build a solid electrification foundation – today. It’s really the next few years that are the most critical for U.S. EV market development.

Think of the new rule like a six-year curve with higher and higher electrification targets every year.

Where is the greatest amount of uncertainty?

Answer: the early years. 2027, 2028, 2029… which is like now in car years. Some model year 2025 vehicles will soon be for sale at dealerships.

Those also happen to be the years that EPA made the biggest downward adjustment to the final rule.

This is smart and essentially what we said to the administration when we suggested they moderate the EV adoption slope.

In other words: pace matters.

Pace matters to automakers. It matters to suppliers, workers and dealers. And it certainly matters to consumers still getting their heads around EVs. (Not everyone lives in California, after all. And even in the Golden State, 75 percent of consumers still buy conventional vehicles).

EPA also provided manufacturers additional time to implement gasoline particulate filter technology on conventional vehicles.

Here’s another thing they did: adjusted the rules around criteria pollutant emissions.

EPA dropped explicit prohibitions on enrichment (that basically protects engine components) so manufacturers can meet consumer expectations for towing, acceleration and other utility.

Taken together, these are positive course corrections from the administration that do two important things.

- First, it sets more reasonable electrification targets in the early years of the rule.

- Second, it won’t siphon an automaker’s capital obligations pledged to EVs toward internal combustion technology (that will eventually phase out). That would be backwards.

Other observations:

Vehicle choice – plug-in hybrids are back…

Speaking of consumers (please reader… DON’T forget about where car buyers should rank in this debate) the new rules provide room for plug-in hybrids as part of the EV transition.

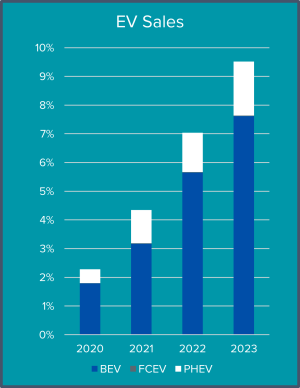

EPA’s original proposal only projected battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in the electrification targets.

But we said plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) – vehicles with both an electric motor and a combustion engine – have a role to play.

Actually, we thought taking this popular and transitional powertrain off the field was… well, not a good idea.

Source: Get Connected Electric Vehicle Report Q4 2023 (coming soon)

After all, what are we trying to solve for?

Is our goal to get Americans to simply buy a different device… or, over time, are we trying to replace petroleum miles with electric miles?

Here the administration recognized what was happening in the marketplace.

The market for EVs is spiky (still growing) and EPA’s proposed regulations were ahead of customers.

And the industrial base, access to critical minerals, and charging infrastructure aren’t close to 100 percent there yet.

Plug-in hybrids are an excellent bridge technology under those circumstances.

Customers like them… and now they count.

U.S. can’t be an island market…

Not everyone is thrilled about the shift to electrification. Skeptical, opposed, whatever.

The truth is… that shift is already underway in every major market around the world.

And U.S.-based automakers export about two million vehicles every year. That’s manufacturing activity that supports American jobs, GDP and national security.

What happens if the U.S. doesn’t pivot and shift its industrial base toward electrification when the rest of the world is clearly heading in that direction?

What if regulatory and policy ping pong renders us unable to produce the EVs that Europe and other markets will mandate… or that China is determined to dominate?

That kind of whipsawing is a recipe for the U.S. to be an island automotive market – a home to yesterday’s technology… but not tomorrow’s.

Who would want that?

Bottom line…

No matter where these EV rules landed, it was sure to require a complete transformation of the U.S. automotive industrial base and a complete transformation of the automotive market.

These emissions rules are the most consequential – and stringent – transportation carbon-reducing policies in history.

They are different – and improved – from what the administration originally announced about a year ago.

Again, don’t just focus on the 2032 EV target… pay attention to the big revisions in the next few years. That’s the story.

And they’re still going to be very, very challenging to achieve.

Moderating the pace of EV adoption in 2027, 2028, 2029 and 2030 was the right call.

It prioritizes more reasonable electrification targets in these next few (very critical) years.

The adjusted EV targets – still an ambitious stretch goal – should give the market and supply chains a chance to catch up and further bypass China.

It buys some time for more public charging to come online, and the industrial incentives and policies of the Inflation Reduction Act to do their thing.

And the big one?

It avoids a potential EV backlash by respecting the American driver (the key to whether this entire experiment rises or falls) and preserves their ability to choose the vehicle that’s right for them.

More to come…

John Bozzella is president and CEO of Alliance for Automotive Innovation.